Shedding light on social workers who pick up the broken pieces each day.

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark– Will and Ty Cassady are siblings who were adopted by Wendy and Richard Cassady in December 2018. Will is a typical 11-year-old boy. He plays video games, loves watching Pokémon and playing basketball in the backyard. He and his brother are surrounded by a family who loves them, but that was not always the case. They know first-hand how important social workers are.

Cassady and his brother were removed from his biological parents’ when he was just 8 years old. He described it as a boring living situation for him and his brother, which consisted of no running water in an insect-infested apartment, so much so that when he would vacuum, he didn’t want to turn the vacuum off because “the roaches would crawl back out.”

In 2019, there were over 34,000 child maltreatment assessments in the state of Arkansas, all of which social workers dealt with. Over 8,000 were found to be true maltreatment cases, like Will and Ty’s—That includes cases related to abuse, child neglect and unlivable housing— Social workers are changing the lives of children who otherwise would be living in those situations, according to the Arkansas Department of Human Services.

Cassady’s mother said, while fostering they would pee themselves wherever they were because they didn’t know what it meant to use the bathroom when they needed to go. “They never got up to go use the bathroom. If they were playing a video game and they needed to pee, they would just pee all over their clothes,” Cassady’s mother said. “They never lived anywhere with plumbing.”

Both boys dealt with trauma. Both went through physical abuse and neglect. Ty experienced a traumatic head injury at 6 months of age, which was a part of a series of abuse-related injuries and was airlifted to Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock because he was turning blue and unresponsive. “His dad’s response was ‘I fed him, then he rolled off the bed and he was lifeless’,” Cassady’s mother said. That’s when social services were called.

Cases like Will and Ty’s are what social workers deal with on a daily basis. The truth is, social workers are heroes of their own kind. They have a lot on their plate. Their workload is piling up, children are in need of saving.

“[Social workers] were some of the first safe people the boys knew,” Cassady’s mother said. “The time the boys spent with them was always positive.”

The capes are still on. Even during a global pandemic.

Abby Hutchins is a program assistant at the Department of Human Services in Fayetteville, Arkansas. The times are hard right now, Hutchins said, and the coronavirus has added to the stress within social work, which has caused a lot of unknowns for Hutchins and her co-workers.

“Our jobs are to keep kids safe and it’s so hard to do when the world is in a crisis,” Hutchins said. Each caseworker in her division has over 100 children on their caseload. They should each have less than 40 children.

Physical visits to children have now been moved to Zoom meetings and Hutchins said it has been hard being apart from “our kids” because “they aren’t just children we’re responsible for. They are the children we love.”

Not only is there more pressure on the social workers, there’s more pressure on the foster parents. Foster children aren’t in school right now, “their routines are messed up and their behaviors escalate,” Hutchins said. Not only that, but the worry of households contracting the virus weighs heavy.

Jeannie Roberts is a journalist at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette who has been fostering for three years. She is a divorced, single mother with three foster daughters, who can’t be named due to foster care rules, a 17-year-old daughter, Austin Roberts, whom Roberts adopted in January after fostering, and a biological daughter, Nikki Davis.

Roberts said she was clueless on how to handle the virus when it hit. It was all so sudden.

“The rules for foster children are different and there was no guidance from [Division of Children and Family Services at the Department of Human Resources] on what to do if your foster child showed symptoms or if you yourself came down with it,” Roberts said.

That’s when the fear truly kicked in for both Roberts and her foster children, “not about getting the virus, but about me getting it and them being pulled out of their home,” Roberts said.

Roberts said she had “the fleeting thought that it would be better if one of the children was the first one to contract the virus instead of me” because then “it would be my choice to keep them in my home and care for them all through to wellness.”

Roberts said her and her foster daughters came down with COVID-19 symptoms that included respiratory issues and fever. During that time, doctors were only testing people with severe symptoms that required hospitalization. “Symptoms spread to the other girls and three of them had to be placed on breathing treatment every two hours,” Roberts said. That’s when doctors decided to test them.

Their tests came back negative, but during the whole process “DCFS from the first moment really went into overdrive,” with dozens of phone calls coming in from different levels in the system. They “offered every kind of help and made sure we had everything we needed,” Roberts said.

Hutchins said that is the reason why she chose this type of work. She has a heart to serve and make a difference. She said her job is to “pick up the pieces of children’s lives other people have broken.”

Hutchins recalled a case she was working on when she started at DHS. It was for a 12-year-old girl who experienced sexual abuse. Hutchins said she was sick to her stomach reading through the file, which had reports from police and the court with “horrific details that no one should have to experience.” The girl is still in the foster care system waiting to be adopted, but Hutchins said she has come a long way.

Hutchins explained how social workers show up to the child’s doctors appointments, therapy sessions and to eat lunch with them at school, and that “kids become more than a random child to us.” We know their stories. We see their growth, and “we get a front row seat to the redemption in their story,” Hutchins said.

Social workers are “working our butts off” to make sure their children are taken care of, and nobody truly knows what social workers do until they’re in their shoes, Hutchins said.

They “truly care about the children and go to seemingly impossible lengths to make sure the children are safe and well,” Roberts said. “They’re hampered though by a critical shortage and underfunding of caseworkers, the massive emotional and physical toll it takes to do this job, and the lack of enough foster homes.”

Hutchins said she wants it to be known that social workers are normal people doing a job that is too big for anyone, but in the lives of Will and Ty, the Robert’s family, and countless others nation-wide, they are true heroes who love those who “were once labeled as ‘unlovable’.”

The Overlooked Heroes

Shedding light on the people who pick up the broken pieces each day. DECK NEEDS TO MAKE CLEAR ANGLE OF STORY. IF THIS IS ABOUT SOCIAL WORKERS THAT NEEDS TO BE STATED

A picture that was drawn by a foster child on Abby Hutchins’ caseload. Fayetteville, Ark. Photo courtesy of Abby Hutchins.

NEEDS DATELINE What comes to mind when you hear the words social worker? AVOID RHETORICAL QUESTIONS Most times, the stereotypical version of a social worker goes something like this—Rude, vague, lazy, THIS IS A STEREOTYPE OF SOCIAL WORKERS? ARE YOU SURE? ISN’T THE STEREOTYPE THAT THEY UNDERPAID SUFFERING MARTYRS? and not to mention the fact that they work in a dark, gloomy building where the lobby is always bombarded with lower-class individuals who let their children run amok—Sounds familiar, huh?

LET’S START SOMEWHERE ELSE WITH THIS STORY. EVEN IF THESE STEREOTYPES WE DON’T NEED TO DREDGE UP THAT UGLINESS. START WITH A PERSON. TELL US A STORY.

The truth is, they’re heroes of their own kind. Social workers have a lot on their plate. Their workload is piling up, children are in need of saving.

The capes are still on. Even during a global pandemic.

Abby Hutchins is a program assistant at the Department of Human Services in Fayetteville, Arkansas. The times are hard right now, Hutchins said. Each caseworker in her division has over 100 children on their caseload. They should each have less than 40 children.

“We are just normal people doing a job that’s too big for anyone,” Hutchins said. “But it’s also the most rewarding thing I could do.”

START WITH THE CASSADY BOYS: Will and Ty Cassady are siblings who were adopted by Wendy and Richard Cassady in December 2018. Will is a typical 11-year-old boy. He plays video games, loves watching Pokémon and playing basketball in the backyard. He and his brother are surrounded by a family who loves them, but that was not always the case. They know first-hand how important social workers are. FINISH THIS FIRST. THAT SOCIAL WORKERS GAVE THEM A NEW LIFE. THEN THIS:

In 2019, there were over 34,000 child maltreatment assessments in the state of Arkansas, all of which social workers dealt with. Over 8,000 were found to be true maltreatment cases, like Will and Ty’s—FIX SYNTAX That includes cases related to abuse, child neglect and unlivable housing— Social workers are changing the lives of children who otherwise would be living in those situations, according to the Arkansas Department of Human Services . FIND US A NEWS PEG. WHY ARE WE READING ABOUT SOCIAL WORKERS NOW? WORK CASSADY INTO THE NUT GRAF

Cassady and his brother were removed from his biological parents’ when he was just 8-years old. He described it as a “boring” living situation for him and his brother, which consisted of no running water, an insect HYPHENATE infested apartment, so much so that when he would vacuum, he didn’t want to turn the vacuum off because “the roaches would crawl back out.”

Cassady’s mother said, while fostering they would pee themselves wherever they were because they didn’t know what it meant to use the bathroom when they needed to go. “They never got up to go use the bathroom. If they were playing a video game and they needed to pee, they would just pee all over their clothes,” Cassady’s mother said. WOW. OH MY GOD. “They never lived anywhere with plumbing.”

Both boys dealt with trauma. Both went through physical abuse and neglect. Ty experienced a traumatic head injury at NO HYPHEN. HYPHENATE ONLY TWO WORDS THAT COME TOGETHER TO MODIFY A NOUN 6-months of age, which was a part of a series of abuse-related injuries and was airlifted to Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock because he was turning blue and unresponsive. “His dad’s response was ‘I fed him, then he rolled off the bed and he was lifeless’,” Cassady’s RANDOM CAPITALIZATION: Mother said. That’s when social services were called.

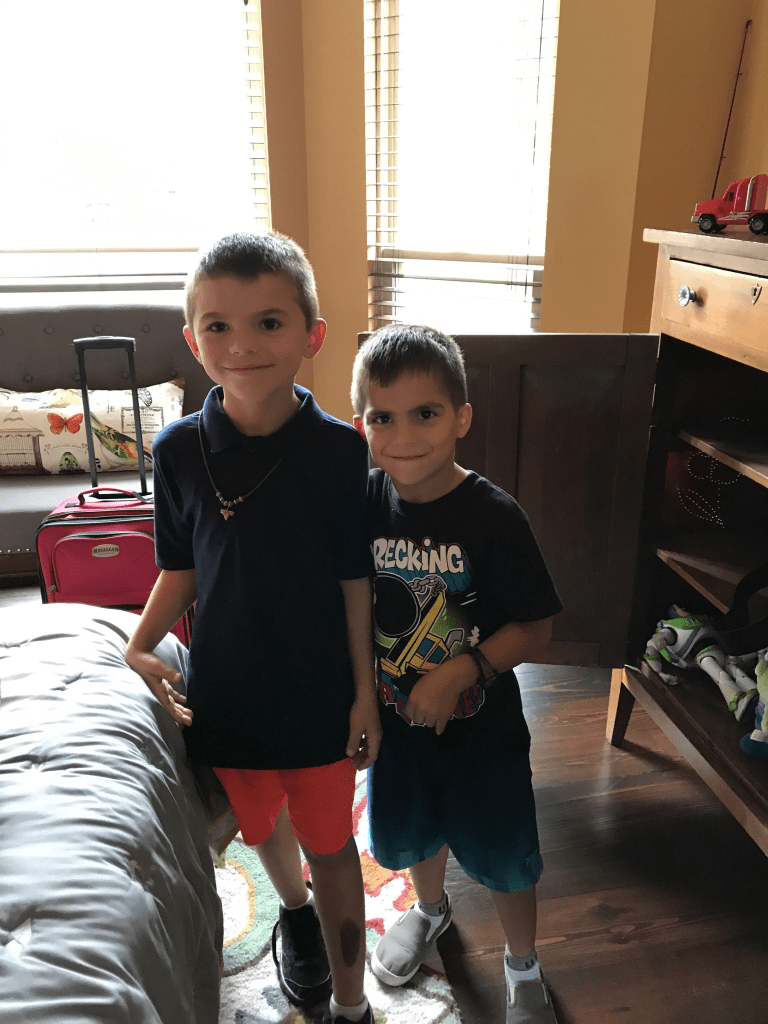

Will Cassady, left, and Ty Cassady, right, on the day they moved in with Wendy and Richard Cassady to begin fostering. Springdale, Ark. August 2017. Photo courtesy of Wendy Cassady. VERY SWEET PHOTO

Cases like Will and Ty’s are what social workers deal with on a daily basis, Hutchins said. She recalled a case she was working on when she started at DHS. It was for a 12-year-old girl who experienced sexual abuse. Hutchins said she was sick to her stomach reading through the file, which had reports from police and the court with “horrific details that no one should have to experience.” WHAT HAPPENED TO THIS GIRL?

Hutchins explained the reason why she chose this type of work. She has a heart to serve and make a difference. She said her job is to “pick up the pieces of children’s lives other people have broken.”

The coronavirus has added to the stress within social work, which has caused a lot of unknowns for Hutchins and her co-workers. “Our jobs are to keep kids safe and it’s so hard to do when the world is in a crisis,” Hutchins said. MAKE THIS THE NEWS PEG. MAKE IT EXPLICIT IN THE NUT GRAF THAT THE VIRUS IS CHANGING THEIR WORK, MAKING DIFFICULT WORK EVEN HARDER. AND BE SPECIFIC HOW. USE CASSADY BOYS AS EXAMPLES OF HOW SOCIAL WORK SAVES LIVES AND THEN EXPLAIN HOW PANDEMIC IS COMPLICATING THAT.

Physical visits to children have now been moved to Zoom meetings and Hutchins said it has been hard being apart from “our kids” because “they aren’t just children we’re responsible for. They are the children we love.”

Not only is there more pressure on the social workers, there’s more pressure on the foster parents. Foster children aren’t in school right now, “their routines are messed up and their behaviors escalate,” Hutchins said. Not only that, but the worry of households contracting the virus weighs heavy.

NEED TO TIE TOGETHER FOSTER PARENTS AND SOCIAL WORKERS. FEELS LIKE A DETOUR. TRY TO KEEP FOCUS ON SOCIAL WORKERS AND THE PANDEMIC:Jeannie Roberts is a journalist at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette who has been fostering for three years. She is a divorced, single mother with three foster daughters, a 17-year-old daughter she adopted in January after fostering, Austin Roberts, THIS IS CONFUSING. IS AUSTIN THE NAME OF THE 17 YEAR OLD? WHAT ARE NAMES AND AGES OF OTHER TWO FOSTER DAUGHTERS? and a biological daughter.

Roberts said she was clueless on how to handle the virus when it hit. She isn’t the legal guardian of her foster daughters. She can’t just take them to the doctor when they’re sick. This was nerve-WRACKINGracking for her.

“The rules for foster children are different and there was no guidance from [Division of Children and Family Services at the Department of Human Resources] on what to do if your foster child showed symptoms or if you yourself came down with it,” Roberts said.

That’s when the fear truly kicked in for both Roberts and her foster children, “not about getting the virus, but about me getting it and them being pulled out of their home,” Roberts said.

Roberts said her and her foster daughters came down with COVID-19 symptoms that included respiratory issues and fever. During that time, doctors were only testing people with severe symptoms that required hospitalization. “Symptoms spread to the other girls and three of them had to be placed on breathing treatment every two hours,” Roberts said. That’s when doctors decided to test them.OH MY GOD. I HAD NO IDEA.

Roberts said they were finally able to get tested and their tests came back negative, but during the whole process “DCFS from the first moment really went into overdrive,” with dozens of phone calls coming in from different levels in the system. They “offered every kind of help and made sure we had everything we needed,” Roberts said.

Jeannie Roberts, left, and her adopted daughter, Austin Roberts, at the White County Court House in Searcy, Ark. for her adoption hearing. January 2020. Photo courtesy of Jeannie Roberts. GREAT PHOTO

Social workers are “working our butts off” to make sure their children are taken care of, and nobody truly knows what social workers do until they’re in their shoes, Hutchins said. TIE THIS BACK INTO ROBERTS SOMEHOW. WHAT ROLE DID SOCIAL WORKERS PLAY IN HELPING ROBERTS GET TESTING FOR HER FAMILY? AND DID THAT EXPERIENCE FORCE THE STATE TO CREATE GUIDANCE FOR COVID?

Hutchins explained how social workers show up to the child’s doctor’s appointments, therapy sessions and to eat lunch with them at school, and that “kids become more than a random child to us.” We know their stories. We see their growth, and “we get a front row seat to the redemption in their story,” Hutchins said.

CUT: So, next time the stereotypical version of a social worker comes to mind, remember this— They’re fighting for children who can’t fight for themselves. Who else is going to do it?

GIVE US A SCENE, A MOMENT THAT SHOWS US THE IMPACT.

GOOD TOPIC. FLESH OUT THE NEWS PEG. KEEP THE FOCUS TIGHT. I LOOK FORWARD TO YOUR REVISION.

LikeLike

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark– Will and Ty Cassady are siblings who were adopted by Wendy and Richard Cassady in December 2018. Will is a typical 11-year-old boy. He plays video games, loves watching Pokémon and playing basketball in the backyard. He and his brother are surrounded by a family who loves them, but that was not always the case. They know first-hand how important social workers are.

Cassady and his brother were removed from his biological parents’ when he was just 8 years old. He described it as a boring living situation for him and his brother, which consisted of no running water in an insect-infested apartment, so much so that when he would vacuum, he didn’t want to turn the vacuum off because “the roaches would crawl back out.”

In 2019, there were over 34,000 child maltreatment assessments in the state of Arkansas, all of which social workers dealt with. Over 8,000 were found to be true maltreatment cases, like Will and Ty’s—That includes cases related to abuse, child neglect and unlivable housing— Social workers are changing the lives of children who otherwise would be living in those situations, according to the Arkansas Department of Human Services.

Cassady’s mother said, while fostering they would pee themselves wherever they were because they didn’t know what it meant to use the bathroom when they needed to go. “They never got up to go use the bathroom. If they were playing a video game and they needed to pee, they would just pee all over their clothes,” Cassady’s mother said. “They never lived anywhere with plumbing.”GOOD VIVID DETAILS ABOUT THEIR LIVING SITUATION

Both boys dealt with trauma. Both went through physical abuse and neglect. Ty experienced a traumatic head injury at SPELL OUT ZERO THROUGH NINE 6 months of age, which was a part of a series of abuse-related injuries and was airlifted to Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock because he was turning blue and unresponsive. “His dad’s response was ‘I fed him, then he rolled off the bed and he was lifeless’,” Cassady’s mother said. That’s when social services were called.

Cases like Will and Ty’s are what social workers deal with on a daily basis. The truth is, social workers are heroes of their own kind. They have a lot on their plate. Their workload is piling up, children are in need of saving.

“[Social workers] were some of the first safe people the boys knew,” Cassady’s mother said. “The time the boys spent with them was always positive.”

The capes are still on. Even during a global pandemic. NICE.

Abby Hutchins is a program assistant at the Department of Human Services in Fayetteville, Arkansas. The times are hard right now, Hutchins said, and the coronavirus has added to the stress within social work, which has caused a lot of unknowns for Hutchins and her co-workers.

“Our jobs are to keep kids safe and it’s so hard to do when the world is in a crisis,” Hutchins said. Each caseworker in her division has over 100 children on their caseload. They should each have less than 40 children. GOOD DATA

Physical visits to children have now been moved to Zoom meetings and Hutchins said it has been hard being apart from “our kids” because “they aren’t just children we’re responsible for. They are the children we love.”

Not only is there more pressure on the social workers, there’s more pressure on the foster parents. Foster children aren’t in school right now, “their routines are messed up and their behaviors escalate,” Hutchins said. Not only that, but the worry of households contracting the virus weighs heavy.

Will Cassady, left, and Ty Cassady, right, on the day they moved in with Wendy and Richard Cassady to begin fostering. Springdale, Ark. August 2017. Photo courtesy of Wendy Cassady

.

Jeannie Roberts is a journalist at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette who has been fostering for three years. She is a divorced, single mother with three foster daughters, who can’t be named due to foster care rules, a 17-year-old daughter, Austin Roberts, whom Roberts adopted in January after fostering, and a biological daughter, Nikki Davis.

Roberts said she was clueless on how to handle the virus when it hit. It was all so sudden.

“The rules for foster children are different and there was no guidance from [Division of Children and Family Services at the Department of Human Resources] on what to do if your foster child showed symptoms or if you yourself came down with it,” Roberts said. STILL NEED TO ATTACH THIS PART OF STORY TO SOCIAL WORKERS

That’s when the fear truly kicked in for both Roberts and her foster children, “not about getting the virus, but about me getting it and them being pulled out of their home,” Roberts said.

Roberts said she had “the fleeting thought that it would be better if one of the children was the first one to contract the virus instead of me” because then “it would be my choice to keep them in my home and care for them all through to wellness.”

Roberts said her and her foster daughters came down with COVID-19 symptoms that included respiratory issues and fever. During that time, doctors were only testing people with severe symptoms that required hospitalization. “Symptoms spread to the other girls and three of them had to be placed on breathing treatment every two hours,” Roberts said. That’s when doctors decided to test them.

Their tests came back negative, but during the whole process “DCFS from the first moment really went into overdrive,” with dozens of phone calls coming in from different levels in the system. They “offered every kind of help and made sure we had everything we needed,” Roberts said.

Hutchins said that is the reason why she chose this type of work. She has a heart to serve and make a difference. She said her job is to “pick up the pieces of children’s lives other people have broken.”

Hutchins recalled a case she was working on when she started at DHS. It was for a 12-year-old girl who experienced sexual abuse. Hutchins said she was sick to her stomach reading through the file, which had reports from police and the court with “horrific details that no one should have to experience.” The girl is still in the foster care system waiting to be adopted, but Hutchins said she has come a long way.

Jeannie Roberts, left, and her adopted daughter, Austin Roberts, at the White County Court House in Searcy, Ark. for her adoption hearing. January 2020. Photo courtesy of Jeannie Roberts.

Hutchins explained how social workers show up to the child’s doctors appointments, therapy sessions and to eat lunch with them at school, and that “kids become more than a random child to us.” We know their stories. We see their growth, and “we get a front row seat to the redemption in their story,” Hutchins said.

Social workers are “working our butts off” to make sure their children are taken care of, and nobody truly knows what social workers do until they’re in their shoes, Hutchins said.

They “truly care about the children and go to seemingly impossible lengths to make sure the children are safe and well,” Roberts said. “They’re hampered though by a critical shortage and underfunding of caseworkers, the massive emotional and physical toll it takes to do this job, and the lack of enough foster homes.”

Hutchins said she wants it to be known that social workers are normal people doing a job that is too big for anyone, but in the lives of Will and Ty, the Robert’s family, and countless others nation-wide, they are true heroes who love those who “were once labeled as ‘unlovable’.”

NICELY WRITTEN. THANKS FOR THE REVISION.

LikeLike